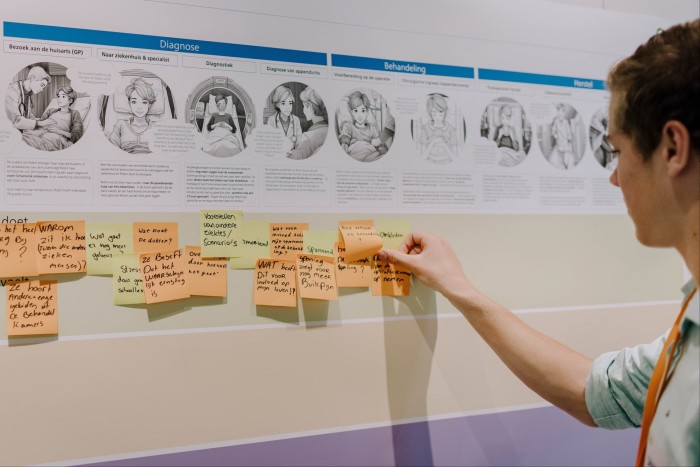

In a large airy room at the headquarters of the Philips healthcare company in Eindhoven, the Netherlands, a group of local teenagers seriously discuss how to improve the care of “Robin,” a patient about their age with appendicitis.

Each step of the journey, from diagnosis to recovery, is illustrated with AI-generated scenarios. But even if the scenario is imaginary, it’s more than just a well-intentioned but ultimately expendable form of community outreach.

Philips is looking to harness the wisdom of this cohort of 13- to 15-year-old digital natives to help it rethink care and identify technologies that can improve the patient experience.

“We’re doing this because if we’re meeting young people, we’re actually looking at the future of healthcare,” says Peter Skillman, who is only the eighth global head of design in Philips’ nearly century-long history. He proudly displays a book of photographs of his predecessors to underline the legacy he has inherited.

The usefulness of this young group is not only in its insight into what the next generation of healthcare professionals and patients will want. It is also his ability to apply open, agile thinking and influence care in the here and now.

Skillman suggests that this is a generation that expects information to be delivered quickly and in an easily digestible form. And its members lack the automatic deference to clinical authority that their parents or grandparents might have shown.

He adds: “They can switch between tasks very quickly and are very adaptable. They are users of emerging technologies [they have a] a very low threshold for trying new things.”

Skillman was previously struck by a comment from one of the teenagers, who recalled that after taking a medical test, she was told to wait for the doctor to come in and read the result. “She said ‘I had to wait so long and the doctor came in and in two minutes he said, ‘everything is fine,'” she recalls. “And she was [asking] ‘why?’ They have no respect for the hierarchy of medical leadership. He thinks that “these people serve me”.

Divided into groups, the young people first talk through the scenarios and explore the feelings they evoke. Certain common themes emerge: concerns about what can go wrong in surgery; the desire to receive information quickly and in a way that they understand; wish to spare parents worry.

They are then moved to another part of the building where Senior Software Architect Jean-Marc Huijskens introduces them to a variety of cutting-edge technologies that will delight any teenager. These include augmented and virtual reality demonstrations [AR and VR] — a simulated, immersive experience used in this case to demonstrate what it’s like to drive while extremely tired — and a machine that allows surgeons to see a 3D image of the heart, allowing them to determine the size of the stent needed to keep the blood vessel open.

Back in the groups, more discussion ensues before the young people present their ideas with shy pride. These include: a “care robot” to ease the sense of insecurity and insecurity often felt by young patients; an AI avatar to prepare them for what to expect from treatment; and a robot “pet” that keeps worried younger patients company. The envisioned inventions would all use generative AI, ensuring that patients can have questions about their hospital spell answered in real time.

Young people’s ideas need to be validated by a wider group, including designers, engineers, patient groups and doctors. However, past experience suggests that at least some may bear fruit.

Skillman cites a session in 2019 when another group of teenagers spent time in one of her innovation labs and learned how catheters are used in hospitals to perform procedures in a less invasive way than traditional surgery.

“They said, ‘I want you to tell me immediately what happened.’ [during the procedure] simply put. Don’t make me speak medically because I don’t understand.” Now the company is using an artificial intelligence program to communicate complicated medical diagnoses in simple language.

Aware that these young people are not only patients, but also the doctors, nurses and healthcare workers of the future, Robert-Jan de Pauw, director of data solutions at Philips, also organizes a meeting for those considering a clinical career. They are asked to try existing and prototype technologies.

According to him, it “takes us about seven and a half to 10 years” to build a new system. So by the time it’s on the market, those teenagers may be old enough to be used by adult doctors.

De Pauw points out the small but telling differences involved in Philips’ design decisions from the information gleaned during these sessions.

For example, when handling remote controls, teenagers, he notes, “use their thumb, while older people tend to use their index finger. We believe it is very important to get input from younger people because they are the future users of the system.”

At the end of their morning immersed in health technology, the two young people at the session witnessed by the FT are buzzing with the new information and perspectives they have gained.

Diede Tyssens 14-year-old Diede Tyssens, who is considering a career as a midwife as an interpreter, says she “loved being able to immerse herself in the medical world”.

Her 15-year-old classmate Anuraag Nayak, who is considering biology or medicine as his future path, says he has “learned a lot. I didn’t even know that stuff [as simulations and VR] existed”.

He recently had his own appendicitis, which made the day’s activities particularly resonant for him: “This project was quite personal,” he says.