Sea anemones catch small animals that drift along the bottom. This species belongs to the order Actiniaria. Credit: SMARTEX/NHM/NOC

Transparent sea cucumbers, pink sea pigs and bowl-shaped sponges are some of the fascinating animals discovered during a deep-sea expedition to the Pacific Ocean’s Abyssal Plains.

In March, a 45-day research expedition to the Clarion Clipperton Zone between Mexico and Hawaii in the eastern Pacific Ocean ended. One of the scientists on board the British research vessel James Cook was Thomas Dahlgren, a marine ecologist from the University of Gothenburg and the NORCE Research Institute.

“These areas are the least explored on Earth.” It is estimated that only one animal in ten species life down here has been described by science,” he says.

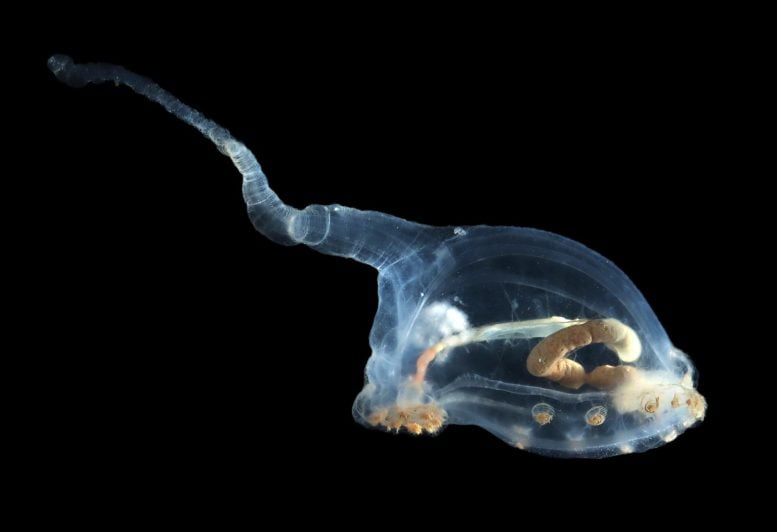

This cucumber with a transparent body belongs to the family Elpidiidae and is called “unicumber”. You can clearly see its guts and that it is eating sediment. We can only guess what the long tail is for, but probably to help it swim. Credit: SMARTEX/NHM/NOC

The study area is part of the Abyssal Plains, which are deep-sea areas at depths of 3,500 to 5,500 meters. Although they make up more than half of the earth’s surface, very little is known about their fascinating animal life.

“This is one of the few times when researchers can be involved in discovering new species and ecosystems in the same way they were in the 18th century. It’s very exciting,” says Thomas Dahlgren.

Abyssal Plains

The ocean floor, which lies between 3,500 and 5,500 meters deep, is called the Abyssal Plains. Despite the name, it is not a completely flat landscape. There are plenty of ridges and small seamounts that can rise several hundred meters from the ocean floor, but in most cases not enough to show up on existing maps.

The environment on these plains is extremely poor in nutrients. The nutrients present are either leftovers from hot springs that lie further out, or expelled from the occasional whale carcass sunk to the bottom. Otherwise, the nutrients come from the productive sea surface several kilometers above, where only about one percent reaches the ocean floor as marine snow.

Sea cucumbers and glass mushrooms

Animals living in these deep sea areas have adapted to life with very little nutrition. Most feed on organic debris, known as marine snow, falling from the more productive area near the surface. As a result, filter feeders such as sponges and sediment feeders such as sea cucumbers dominate this animal population.

“The lack of food causes individuals to live far apart, but the species richness in the area is surprisingly high. We see many exciting specialized adaptations among animals in these areas,” says Dahlgren.

One of the species discovered on the expedition was the pink sea pig, or ‘Barbie Sea Pig’, as it is called in English. It got its name because of its pink color and small feet. Credit: SMARTEX/NHM/NOC

Using a remotely operated vehicle (ROV), the research team photographed deep-sea life and collected samples for future studies. One of the species caught on camera was the bowl-shaped glass mushroom, an animal believed to have the longest lifespan of any creature on Earth. They can live up to 15,000 years.

Another species discovered on the expedition was the pink sea pig, a sea cucumber of the genus Amperima. This species moves very slowly with its tube feet across barren plains in search of nutrient-rich sediments. The growths on the anterior end of the underside are modified legs used to stuff food into the mouth.

“These cucumbers were some of the largest animals found on this expedition. They act like vacuum cleaners on the ocean floor and specialize in finding sediments that have passed through the fewest stomachs,” says Dahlgren.

Threatened by mining

The aim of the expedition was to map the biodiversity of the area where deep mining of precious metals used in solar panels, electric car batteries and other green technologies is planned. Several countries and companies are waiting for permission to mine these metals bound in mineral nodules lying on the ocean floor. Scientists want to find out more about how mining might affect the ecosystem, record existing species and find out how the ecosystem is organized.

“We need to know more about this environment to be able to protect the species that live here.” Today, 30% of these considered marine areas are protected, and we need to know if this is enough to keep these species at risk of extinction,” says Dahlgren.