Andrew Cunningham, chief executive of green hydrogen company GeoPura, likens the challenge of expanding the sector to gridlock.

“It’s about breaking the ‘chicken and egg,'” he says. There’s a “cycle of people not building hydrogen capacity because they’re not sure who’s going to use it. . . and [of] people who don’t develop abilities need hydrogen [because of the lack of supply]”.

GeoPura has partnered with Siemens Energy to develop environmentally friendly hydrogen or renewable energy alternatives to replace diesel generators in industries ranging from live music to construction. Cunningham, previously a founder of other technology start-ups, self-funded GeoPura after realizing the world’s “overwhelming” dependence on diesel generators.

Green hydrogen is produced by splitting it from water using an electrolyser powered by electricity produced from renewable sources. GeoPura’s business model involves producing hydrogen this way, as well as building fuel cells that use the gas to generate more electricity.

The business was launched in 2019 at the Goodwood Motoring Festival in West Sussex, southern England. He powered part of the event with his hydrogen generator and attracted the interest of potential clients. After years of his own research and investment, this proved to be a turning point for Cunningham.

“It gave me the confidence to break the cycle and actually buy an industrial electrolyser [and to] buy trailers that allow you to move hydrogen,” he explains.

After proving that the concept worked, the next step was to scale the business and secure funding from outside investors. GeoPura pulled it off earlier this year – closing a funding round that raised £56m, including a £30m commitment from the UK’s state-owned Infrastructure Bank. Previous customers have included National Grid and the BBC.

Cunningham’s carefully phased approach highlights the concerns that still surround hydrogen innovation. Gas is seen as a possible panacea as countries rush to decarbonise their economies, but it has also faced setbacks as projects that could prove its long-term viability fail to get off the ground.

It’s a common problem across industries that claim to have potential solutions to help countries reach net zero goals. Governments are often quick to set targets – such as phasing out diesel and petrol cars – but slow to provide funding and regulations to facilitate behavioral change and the formation of new industries.

In the case of green hydrogen, cost-effective production has proven elusive, as high inflation and insufficient subsidies have made it difficult to produce the required electrolyser systems.

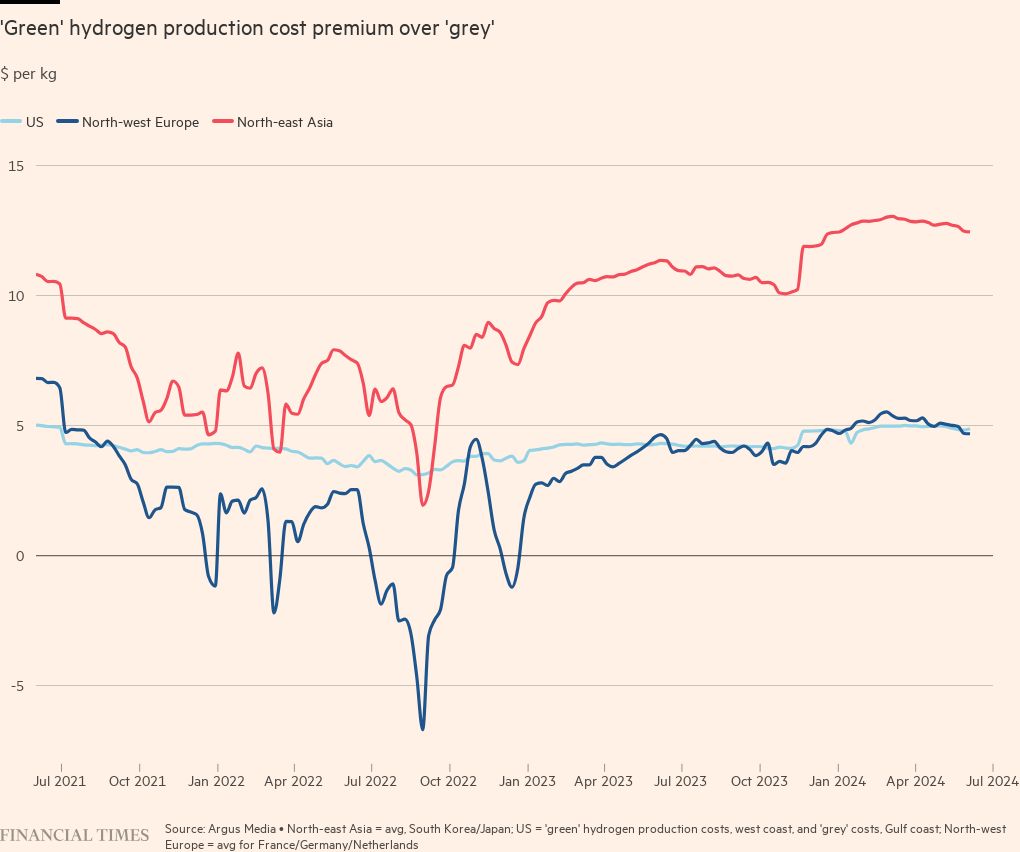

Most of the hydrogen currently used is so-called “grey” hydrogen extracted from natural gas, which releases carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. Green hydrogen doesn’t involve natural gas—but it’s more expensive to produce, and costs are rising rather than falling.

Government support – which is needed to support the supply chain of gas production, storage and transport – has been slow around the world, despite widespread support for the technology as a way to decarbonise energy-intensive industries such as long-haul transport.

$5Cost of hydrogen production per kilogram

Earlier this year, the International Energy Agency said that renewable energy capacity dedicated to hydrogen would grow by 45 GW between 2022 and 2028, 35 percent less than the capacity it predicted a year earlier, suggesting that momentum is being lost.

Building electrolyzers, which use electricity to split water into hydrogen and oxygen, is usually the most expensive step in developing green hydrogen. And it is these costs that threaten efforts to make green hydrogen more competitive against hydrogen produced by dirtier methods.

Sourcing cheap components from China, a leader in clean hydrogen development, could help with costs, but remains problematic due to geopolitical tensions. Western governments have instead sought to develop local supply chains and reduce dependence on a country they see as a competitor. Even so, the cost of producing green hydrogen is still about $5 per kilogram higher than gray hydrogen, making it three times more expensive to produce – according to data company Argus Media.

“If renewable hydrogen is to take off seriously, this cost gap will need to be reduced, which will not be easy and requires a combination of scaling effects, efficiency gains and government subsidies,” says Stefan Krümpelmann, global head of hydrogen pricing at Argus.

He points out that while the number of electrolyzer factories slated for construction has increased, not all planned projects will be completed and “production could be hampered by bottlenecks for individual components.”

Some projects just don’t happen at all. In the latest blow to ambitions to switch to hydrogen, the British government last month shelved plans for Britain’s biggest trial – using the gas to heat up to 10,000 homes – and scrapped two smaller trials last year.

Industry bodies the Energy Networks Association and Hydrogen UK found last year that no major low-carbon hydrogen production projects had reached a final investment decision, despite the country’s target of 10 GW of generation capacity by 2030.

FT Live Hydrogen Summit

It features panel discussions and interviews with senior industry experts and FT specialists. Register to watch online June 12 or watch later.

“Seeing is believing,” says Clare Jackson, CEO of Hydrogen UK. “While we have some smaller projects in the UK, we have yet to see the first large-scale project. We have to start the first projects [because] you have to have somewhere to scale from.”

Fredrik Mowill, chief executive of Hystar, a Norwegian electrolyser developer, admits that some of the “hype” around hydrogen has died down, but says a reduction in the number of “noble” projects would leave room for better alternatives.

Hystar recently signed a supply deal with Johnson Matthey, a London-listed technology group that makes vehicle catalysts, to support the production of green hydrogen – showing there may be demand for energy technologies that are compatible with the decarbonisation agenda.

This article has been amended to show that the cost of producing green hydrogen is about $5 per kg more than that of gray hydrogen.