They once carried the sun god across the sky, guarded golden treasures, and even protected mighty Zeus with their sharp beaks; griffin myths flourished in many ancient civilizations and continue in popular culture to this day.

The prevalence of such monstrous beak-like hybrids in various cultures has led some researchers to believe that the inspiration for these fantastic animals lies in reality, attributing the origin of their mythical existence to the discovery of fossilized dinosaur bones in Asia.

Two scientists from the University of Portsmouth have now put forward their case, arguing that the dinosaur-griffin origin story is itself a myth.

“Not all mythological creatures require explanation through fossils,” says paleontologist Mark Witton.

“Referring to the role of dinosaurs in the griffin tradition, especially species from distant lands such as protoceratops, not only introduces unnecessary complexity and inconsistencies into their origins, but also relies on interpretations and suggestions that do not stand up to scrutiny.”

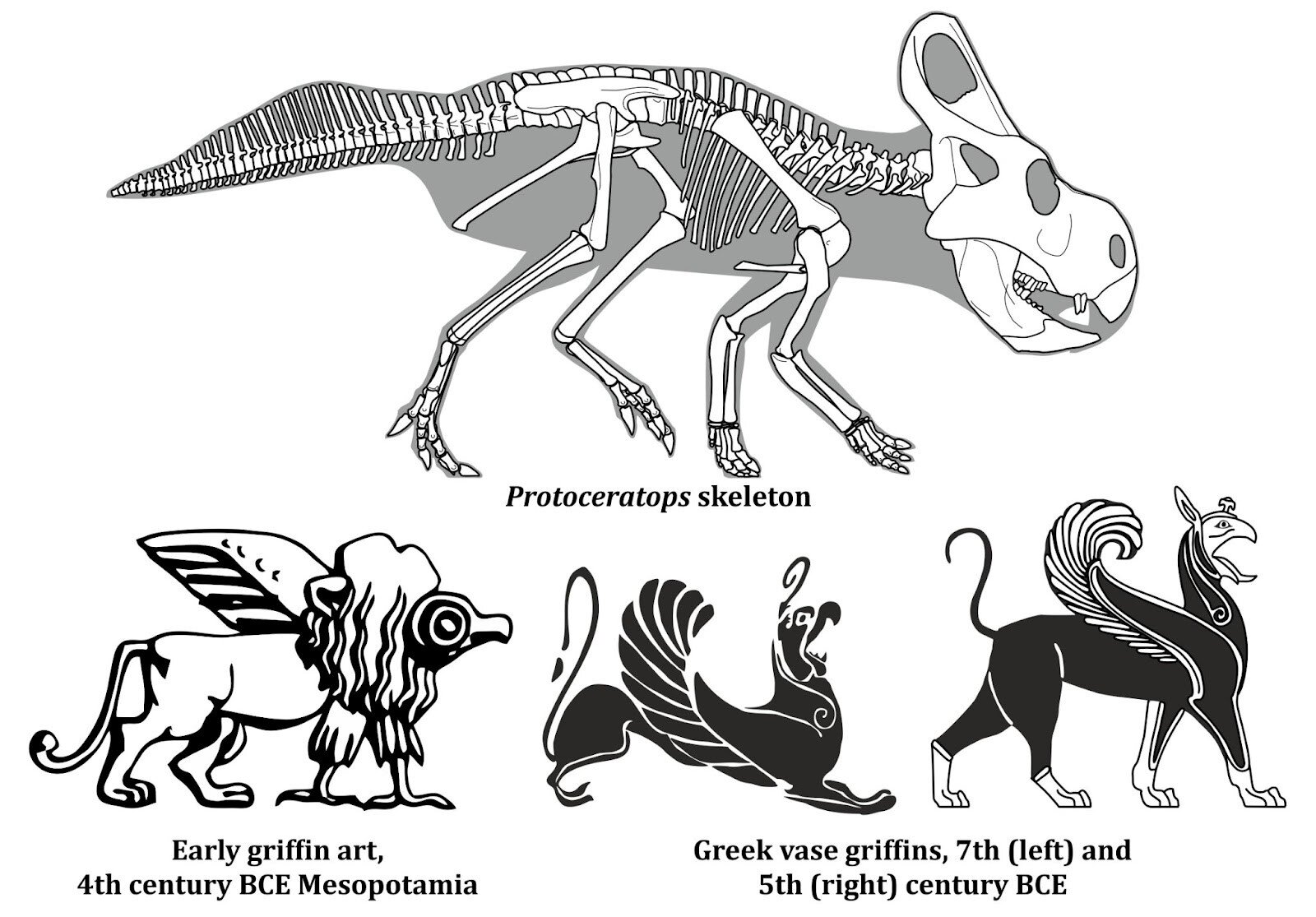

Stories of a beast with the head and forelimbs of a raptor and the body of a lion were attributed by ancient Greek and Roman authors to Central Asia. The spread of such stories along international trade routes led classical folklorist Adrienne Mayo to suggest about 30 years ago that they were imagined by Scythian gold miners who encountered beaked dinosaurs like Protoceratops. This has since become a popular theory of how the griffin myths began.

Reevaluating the fossil record, Witton and his colleague Richard Hing found a number of inconsistencies in this idea.

Griffins were considered protectors in ancient Greece, often associated with guarding hoards of gold – hence the suggested association with gold miners.

There’s one problem: Protoceratops fossils have never actually been found near gold.

“There is an assumption that dinosaur skeletons are discovered half-exposed, lying almost like the remains of recently deceased animals,” explains Witton. “But generally speaking, only a fraction of an eroding dinosaur skeleton will be visible to the naked eye, unnoticed by all but sharp-eyed fossil hunters.”

What’s more, there was a myth of griffins in the Mediterranean, as depicted on a Mycenaean vase from at least the 12th century BC, hundreds of years before reports of dinosaurs could reach the same area.

Witton and Hing also point out that dinosaurs like Protoceratops are only griffin-like in having four limbs and a beak.

“There’s nothing wrong with the idea that ancient people found dinosaur bones and incorporated them into their mythology,” explains Hing.

“But such suggestions must be rooted in the realities of history, geography and paleontology. Otherwise, they are just speculation.”

There are examples of geomythology that are based on bits of truth. For example, stories about magical stone swallows with healing properties flying freely during thunderstorms they probably will mollusk fossils from the Chinese Devonian era which they resemble outstretched bird wings.

Later in their history, fossil relics were also associated with griffins. During the Middle Ages, the horns of ungulates and extinct rhinoceroses were identified as the claws of a mythical beast. But that was centuries after the griffin myths were well established.

An outline impressed into clay from an engraved Mesopotamian seal found in what is now Iran is the oldest known depiction of a gryphon, dating back to 3000 BC

“Everything about the origin of the griffin is consistent with the traditional interpretation of them as imaginary animals, just as their appearance is entirely explained by them being chimeras of large cats and birds of prey,” Witton concludes.

Sometimes fantasy is just that, even if it is shared across a vast amount of time and cultures.

This research was published in Interdisciplinary Scientific Reviews.