A view of the ruins of the Barbegal Mill complex in 2018. Credit: Robert Fabre

Archaeologists face a major problem when they intend to obtain information about buildings or facilities of which only ruins remain. This was a particular challenge for the remains of Roman watermills at Barbegal in southern France, which date back to the 2nd century AD.

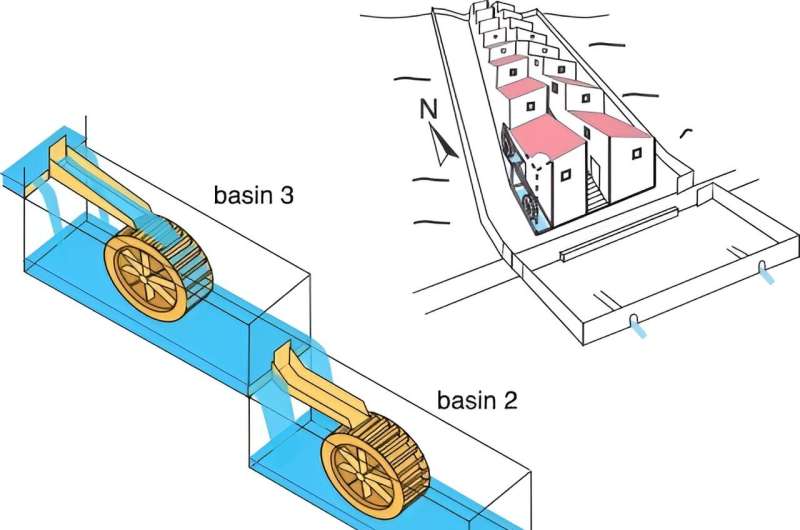

This unique industrial complex consisted of 16 waterwheels located in parallel rows, eight on the east side and eight on the west side, which were operated in a waterfall-like arrangement. From these now meager ruins, little could be inferred about the site at first – except that the wheels were supplied by an aqueduct that brought water from the surrounding hills.

A coin issued during the reign of Emperor Trajan discovered in a basin above the mill site, as well as the structural characteristics of the site, indicate that the mill was in operation for about 100 years. However, the type of mill wheels, their functions and how they were used have remained a mystery to this day.

Carbonate fragments provide remarkable information

Professor Cees W. Passchier and Dr. Gül Sürmelihindi of the Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (JGU), in collaboration with colleagues from France and Austria, have now revealed the history of the mill complex using calcium carbonate deposits, which are now stored in the Arles Archaeological Museum.

These deposits formed towards the end of the roughly 100-year operational life of the Barbegal watermills on the sides and base of the wooden supply system that carried water to the wheels.

“We show that it is possible to reconstruct the history of the water mill on the basis of such carbonate deposits to a large extent,” stated Passchier, leader of the JGU team. First, the researchers had to put some of the 140 pieces deposited together like a jigsaw puzzle, then analyzed the layers using various techniques, including mass spectrometry.

Sketch of Barbegal mill complex with three water reservoirs with mill wheels and water courses. The lower bowls probably had spigot drives. Credit: Cees Passchier

The wooden water wheels and gutters were replaced

The researchers have now published their results in Geoarchaeology. “For example, we were able to demonstrate that wooden water wheels and water channels had to be replaced after three to eight years. In at least one case, the old water wheel was replaced with a larger one,” said Passchier.

Scientists drew this conclusion from the unusual shape of the carbonate deposits that formed in the water channel. While the lower and earlier layers indicate that the water levels must have been relatively low originally, the upper and later carbonate layers indicate a higher level.

Scientists rejected the possibility that originally less water flowed through the water channel, which was subsequently increased. They found that—for a gently sloping water channel and a low water level—the amount of water supplied would not be sufficient to power the mill wheel.

Therefore, the slope of the water bed had to be changed, from the originally steeper angle with a low water level to a shallower slope transporting water at a correspondingly higher level.

“The whole structure of this watermill had to be modified,” Passchier said. “If you raise the water channel by yourself, the water tends to splash and lose power to drive the wheel effectively. So when you raise the water channel, you also need a bigger water wheel.”

In fact, part of the carbonate deposit formed on the water wheel confirms this conclusion, since it does not contain all carbonate layers, but only those from the last years of operation.

A carbonate fragment from the Barbega mills, formed on the wood of the mill machine, with wood prints and traces of woodworking. Credit: Philippe Leveau

The results of the isotopic analysis provide evidence of the lifetime of the mill

Using isotopic analysis of the carbonate layers, the researchers were even able to determine the operating periods before which parts of the mill required restoration. Carbonate contains oxygen, and the relative ratios of oxygen isotopes vary with the temperature of the water. Based on the isotopic composition in the carbonate layers, the scientists were able to infer water temperatures and thus identify the seasons in which the layers were deposited.

They concluded that carbonates from samples in the Arles Archaeological Museum had been deposited in water channels for seven to eight years.

“The uppermost and therefore the youngest carbonate layer contains mollusk shells and wood fragments, which shows that the mill must have been abandoned and decaying at the time. The water continued to flow for a while, so carbonate deposits continued to form, but the water channels ceased to be maintained,” he said Passier.

Scientists were able to answer yet another question. It was not previously known whether the mills were operated in combination by a single operator, or whether the 16 waterwheels were used independently of each other.

Judging by the layers of the three water channels examined, which are clearly different from each other, the mills were in operation separately – at least towards the end of their life. Additionally, the west side of the complex was abandoned earlier than the east side.

Finally, long pieces of carbonate from the water channels were later used as separator screens in the water tank for other industrial purposes after the mills had already been abandoned.

More information:

Cees W. Passchier et al., The Operation and Decline of the Barbegal Mill Complex, the Largest Industrial Complex of Antiquity, Geoarchaeology (2024). DOI: 10.1002/gea.22016

Provided by Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz

Citation: Carbonate layers provide insight into world of ancient Romans (2024, July 1) Retrieved July 2, 2024, from https://phys.org/news/2024-07-layers-carbonate-insight-world-ancient.html

This document is subject to copyright. Except for any bona fide act for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.