Blackstone Group became one of the largest buyers of a type of bank loan that became a lifeline for the private equity industry and exposed the company to risks generated by its own business.

The world’s largest buyout group, which manages more than $1 trillion in assets, last year became a big investor in risk-transfer products backed by short-term loans that private equity fund managers use to close deals while they wait to receive cash from their supporters.

Because of its sheer size, Blackstone has assumed the risk on credit lines associated with its own buyout funds, even though the firm said they make up only a “single-digit percentage” of the portfolios it has exposure to.

Such transactions increase the private equity behemoth’s exposure if the investor was unable or unwilling to finance its commitment.

“The unusual thing about Blackstone is that it’s a bit circular,” said one large SRT investor. “They provide protection for themselves.

The closing of the deals underscores how convoluted and interconnected the private equity industry has become, and how new risks can be created in less regulated corners of the financial system.

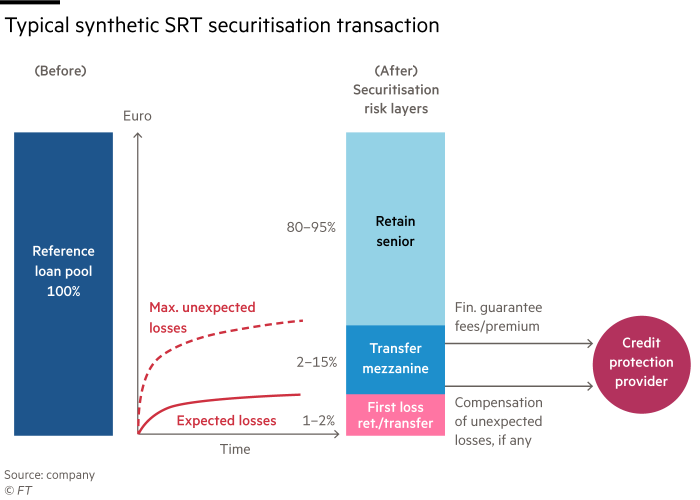

Banks in Europe and the US are finding investors willing to take on some of the default risk of their loan portfolio in so-called significant risk transfer (SRT) transactions.

Such risk transfer transactions allow lenders to reduce the amount of capital that regulators require them to hold, thereby increasing returns.

Blackstone recently became a large investor in SRTs backed by underwriting lines, which are short-term loans used by private equity funds to close deals before receiving cash from their backers.

For several years, private equity firms have financed their buyouts of companies with debt provided by their own credit funds. SRT’s recent transactions, which may themselves be partially financed by bank debt, come amid growing concerns among regulators about the lack of transparency in private markets.

Jonathan Gray, president of Blackstone, told investors in an April earnings call that the group was a “market leader” in SRT. He highlighted underwriting lines as an area of particular concern as they are considered safe assets.

“The most active area so far has been subscription lines, which . . . in the last 30, 40 years they have had virtually no failures. So we like the area,” he said.

Blackstone disputed the circular nature of the risk, saying its investors were “the counterparty to the ultimate risk to which the lender is exposed”. It noted that its investors have never missed a capital call in its 40-year existence.

The group added that its funds made up a “single-digit percentage of the portfolios on which we provided SRT” and that all of its underwritten SRT series “were in highly diversified portfolios”.

The Wall Street-listed group bought the assets through its Blackstone Multi-Asset investment unit, which manages hedge fund-type investment strategies, according to people briefed on the matter.

Banks typically use SRTs to purchase default protection on a pool of loans. This can be done either through a traditional cash transaction, where the assets are moved into a special investment vehicle that issues bonds, or through a derivative product, while the lender holds the assets on its balance sheet.

Asset managers and hedge funds were also among the biggest buyers, including the $244 billion Dutch pension fund PGGM and New York-based firm DE Shaw.

The market for these products first developed in Europe after the 2008 financial crisis, when lenders were asked to meet stricter regulatory capital requirements. US banks became more active last year after the Federal Reserve gave a general green light to bailout deals.

The International Association of Credit Portfolio Managers estimates that 89 SRT transactions were completed worldwide last year for loans with a total value of €207 billion. About 80 percent of these were business loans, with the rest made up of debt such as subscriptions, car loans and trade finance loans.

While private equity credit facilities make up a small part of the SRT market, they have become popular because they are considered relatively safe.

“The thing about underwriting is that it’s an asset class that historically hasn’t lost,” said Frank Benhamou, risk transfer portfolio manager at Cheyne Capital. “They tend to have a low price, so investors who are in this trade often use a bit of leverage to increase returns.”

Through SRT, Blackstone is exposed to the risk that large investors such as pension funds and sovereign wealth funds will refuse to meet capital requirements when the loans mature, usually within a year. The investor could run out of cash or face complications such as penalties or fraud.

While no limited partners ever defaulted, even during the 2008 financial crisis, potential buyers were scared off by the lower diversification of underwriting lines compared to corporate loans.

“While we recognize that credit risk is low for underwriting lines, there is a risk that we cannot quantify and value,” said one investor who has been in the SRT market for more than a decade.

The loan pool for underwriting lines is smaller than traditional asset classes, so “the idiosyncratic risk is the sensitivity of your yield to one side. . . and there is a higher risk of fraud that is difficult to value,” they added, referring to the limited number of private equity funds they would be exposed to.

Another SRT investor pointed out that there are somewhere between 10 and 30 funds in a typical underwriting transaction, creating more concentrated risks.

The rise of these debt products has also revived fears of an unforeseen chain of events, with banking analysts and some policymakers debating whether banks selling SRTs have fully protected themselves. In April earnings, Evercore ISI analyst Glenn Schorr asked Blackstone’s Gray if the SRT explosion carries hidden risks, as it did during the global financial crisis.

This type of deal “chills us, it reminds us about 16 years ago,” Schorr said, referring to the off-balance sheet entities that banks used during the crisis to lighten their overburdened balance sheets. Gray said the firm conducts transactions in a “responsible manner.”