Peter Swain’s electric vehicle company has barely registered as a minnow in the UK car industry, but the Midlands-based entrepreneur says he is already eyeing expansion into the US.

The founder of RBW Electric Cars says the incentives available across the Atlantic put the UK offer in the shade. “There’s so much help we can get everywhere – except in our own backyard,” said Swain, whose small Lichfield-based company makes battery-powered classic cars.

Rachel Reeves, the UK’s new chancellor, vowed on Monday to turn Britain into a “safe haven” for business investment as she sought to tout the country for its stability, in contrast to the political chaos in France.

But business leaders and former ministers have warned that a Labor government faces an extremely difficult task in changing the UK’s reputation and have called for a far-reaching change in the way Whitehall does business.

Lord Peter Mandelson, former Labor business secretary, said that with public borrowing severely constrained, mobilizing private sector capital would be sine qua non for the new government.

“If we think we can succeed by getting anything out of this ‘half truth’ given the self-imposed handicap of Brexit and no longer being part of the EU single market, we are fooling ourselves,” Mandelson said. “Everything has to be completely right, not partially. The new government will have to realize that.”

British businessmen warn the country faces formidable competition from other major markets with deeper-pocketed governments. Years of political upheaval and the upheaval of Brexit have left a lasting legacy, they said.

According to the Institute for Public Policy Research, the UK has languished at the bottom of the G7 total investment table for 24 of the past 30 years, while new foreign direct investment projects are at an almost 12-year low.

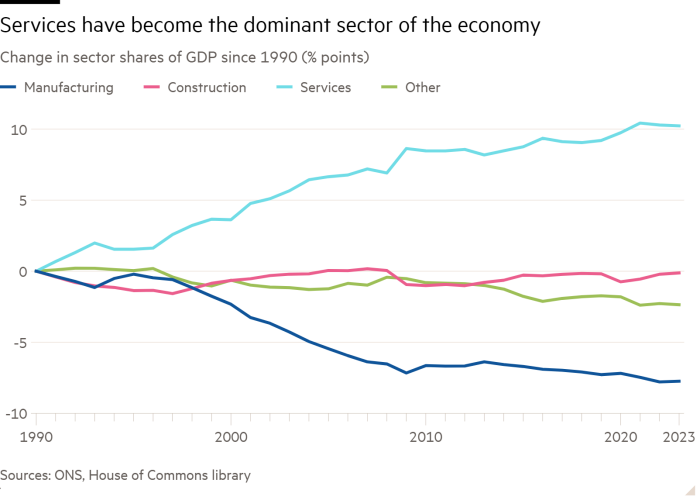

Labour’s pursuit of a new British economic model will mean a greater role for a more strategic state under Reeves’ “securonomic” approach, including – in a sharp departure from the philosophy of former prime minister Rishi Sunak – the creation of a formal industrial strategy that prioritizes sectors with the UK’s comparative advantage.

The notion that government must take an active and strategic role in managing the economy reflects a global trend toward greater state intervention, epitomized by US President Joe Biden’s deflationary law.

It represents a sharp departure from recent practice under the Conservatives. The industrial strategy published by Theresa May’s government in 2017 was shelved by her successor Boris Johnson four years later.

Greg Clark, the former Tory business secretary, said uncertainty over the UK’s post-Brexit business model necessitated a clear strategy set out by the government. “One of the consequences of Brexit is that it’s even more important to have a coherent industrial strategy so that people know what you’re about,” he told the Financial Times. “How can they know if you don’t tell them?”

Under Labour’s approach, the new industrial strategy will focus on areas such as advanced manufacturing, creative industries and green technology. Jonathan Reynolds, the incoming business secretary, said last month that the strategy would be owned by the whole of Whitehall, not just the trade department.

Business and local government representatives will be directly involved in delivering Labour’s five policy ‘missions’, alongside new umbrella bodies – including the Industrial Strategy Board, the UK Infrastructure Council and the Innovation Regulator – to make the journey easier for investors.

A £7.3 billion National Investment Fund will be set up as a co-investor in key projects, with further details due to be announced this week.

Management said change was urgently needed, including simpler processes for applying for innovation support, faster planning decisions and the easing of barriers such as overpriced visas.

Rowan Crozier, chief executive of Birmingham metals company Brandauer, said public support for small producers like his was not only hard to find, but in his experience less plentiful since Brexit. The country needs a “proper, locked-in strategy”, he said. “It’s a bit haphazard.

Sir Keir Starmer’s government is not the first to promise to overcome bureaucratic hurdles. Giles Wilkes, a former policy adviser to May who worked on her 2017 industrial strategy, said the biggest source of uncertainty was the government’s very departmental structure, which made it difficult to overcome the obstacles managers faced.

Lord Richard Harrington, author of the 2023 report on boosting inward investment, said one answer was to create a “concierge service” for big investors that would match the process in other countries.

This would include the ability to assemble land, speed up planning approvals and deliver critical infrastructure such as network connections or secondary roads, all of which will require the “whole of government” approach promised by Reynolds.

Britain, Harrington said, needs to look at areas in which it has a competitive advantage and then come out with packages that attract foreign players to invest, while doing more to help UK-based companies expand at home.

“We can’t be good at everything, but there are sectors [where] the government needs to provide some infrastructure – it could be skills and training, it could be land for cluster development,” he said. “This is very much a part of modern capitalism. We have to do it because our competitors are doing it.”

Labor has promised to focus on the transformative potential of new industries such as life sciences, quantum computing and artificial intelligence. These are areas where the UK has a strong research base but has failed to create the essential conditions for growth clusters – for example around Cambridge, which is constrained by a lack of water and transport infrastructure.

Dan Thorp, chief executive of Cambridge Ahead, a pro-growth group, said Labor faced a daunting task in connecting with investors.

“National cooperation is critical. So with water, that means the Environment Agency, local authorities, water companies and the regulator Ofwat all working together to provide the capacity and give the confidence the industry needs to invest. And then we need the same for energy and transport,” he said.

But experts warn that the UK will have to make a leap-change in its international competitiveness as it is no longer a gateway to the EU’s single market. The head of pharmaceutical giant Eli Lilly recently warned that rival economies such as the US and Ireland offer much faster factory construction times as well as a skilled workforce.

Angus Horner, who founded and expanded the Harwell Science and Innovation Campus south of Oxford in 2013, said part of the government’s job was to reaffirm the need to be competitive. “We have become a nation of process, instead of focusing on output and victory,” he added. “There is something cultural that has shifted.

In the run-up to the election, Starmer and Reeves repeatedly raised expectations that their trade strategy would deliver quick dividends with the aim of growing the G7 as quickly as possible.

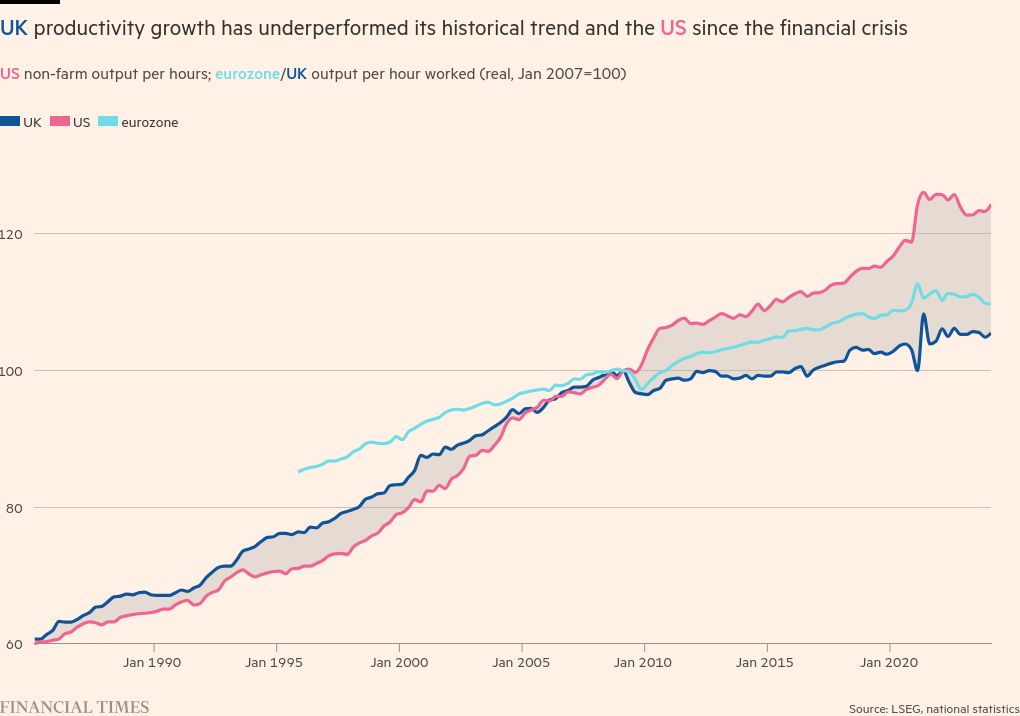

But economists are far from convinced, as it would mean a significant boost to productivity and the Office for Budget Responsibility’s estimates of potential GDP, when many analysts are warning of a downgrade.

The IMF expects annual growth to peak at a maximum of 1.7 percent in the second half of the decade. According to the Institute for Fiscal Studies think tank, GDP per head was almost £11,000 lower than if it had continued on its 2008 trend, underscoring the economic mountain the country has to overcome.

JPMorgan’s Allan Monks said in a note that while low-cost policies such as planning reforms to speed up construction projects could be a catalyst for private sector investment, there are reasons to be skeptical.

The UK has already reaped many of the fruits of deregulation, he added, in areas such as product market regulation. And while Labor has suggested it could remove the barriers to growth created by Brexit, the outcome of any talks with Brussels on closer ties is likely to be modest.

Mandelson called on Labor to be bold in delivering on the party’s growth agenda. “It’s not the hard left I’m worried about,” he said. “It’s something potentially worse. Softness. Compromise. Fudge.”

Data visualization by Keith Fray