Stay informed with free updates

Simply log in to Global inflation myFT Digest – delivered straight to your inbox.

In 2022, author, chef and anti-poverty campaigner Jack Monroe started a mansplaining epidemic by suggesting that the cost of British branded food was rising faster than average food prices. The ONS modified its survey in response and then took months to say it did not see a problem.

Much about the ONS methodology seemed weak even at the time. And after two years, his main finding looks completely wrong.

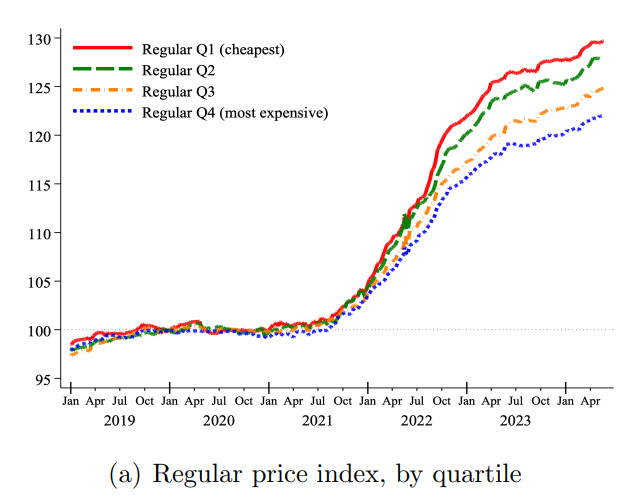

An NBER working paper by Alberto Cavallo and Oleksiy Kryvtsov released last month finds “ample evidence” that the so-called cheap flake is a global phenomenon. Their study of food prices through recent increases in inflation shows that prices of low-cost goods have risen 1.3 to 1.9 times faster than prices of more expensive brands:

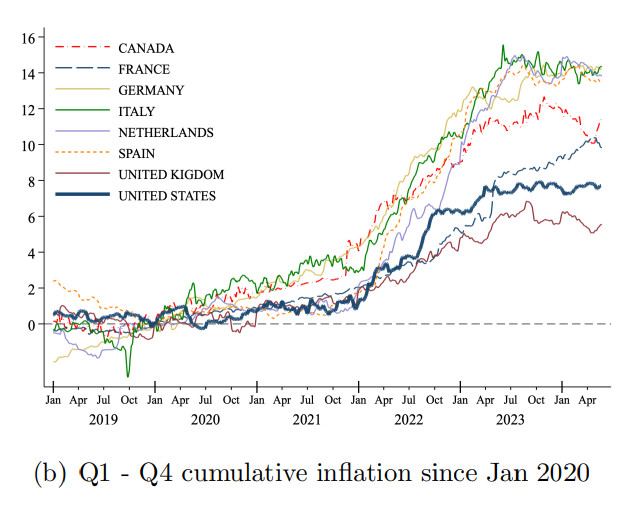

Cheapflation was seen in all ten countries sampled, the researchers say. The UK had the smallest cheap-to-expensive inflation premium, at 6 percentage points, compared to 14 percentage points in Germany, Italy and the Netherlands:

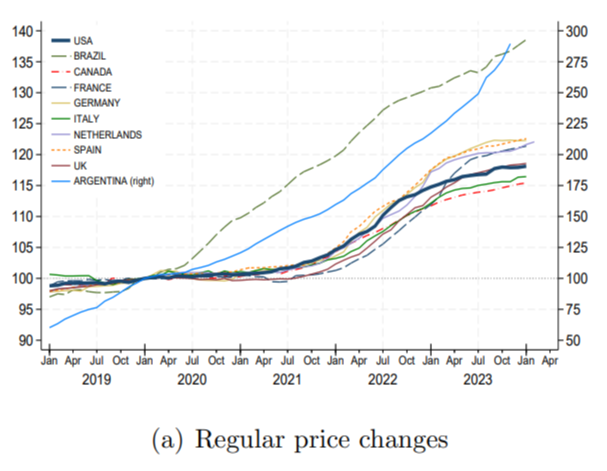

Cavall and Kryvtsov’s data set is much wider than the ONS study of just “30 everyday foods”. Cavallo is the co-founder of Pricestats, a private data provider, so between 2018 and 2024 he was able to use unit prices for more than 2.1 million products for sale at 91 omnichannel retailers.

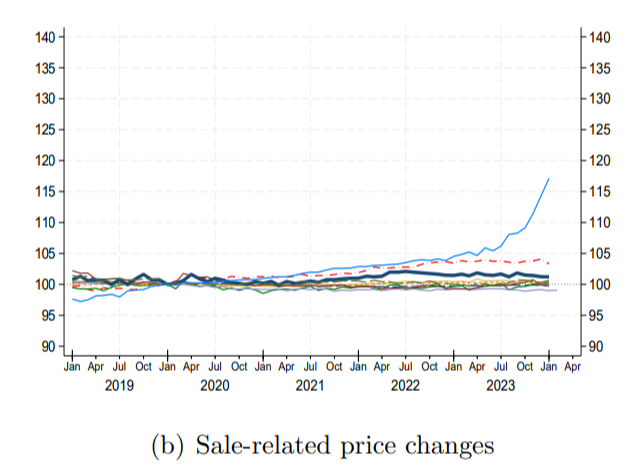

The huge sample size also allowed the researchers to measure whether shoppers were able to save money in a given period by choosing which products were on sale that week.

For anyone with time to spare and no brand loyalty, there were savings to be found. Grocers pushed through price hikes on common goods during the surge, but kept their promotions aggressive, with discounts having little effect on overall inflation:

Such benefits rarely apply to value ranges, which tend to be discounted only as their use-by date approaches.

Based on data from the NielsenIQ Homescan panel on the Canadian grocery market, Cavallo and Kryvtsov estimate that customers will reduce their average unit price by 4.1 percentage points by using discounts. But by moving to “cheaper” brands – those with lower non-sale prices – their average unit price increased by 2.8 percentage points.

None of this should come as a surprise, as low-flation trends are relatively easy to explain. On the supply side, discount brands are exposed to global supply chains and input commodity prices with little room for margins to absorb rising costs. On the demand side, rising inflation and falling real incomes mean a shift in spending towards cheaper products.

A pandemic-era stimulus aimed at low-income families contributed to this increased relative demand, write Cavallo and Kryvtsov:

Finally, although households may have saved by purchasing cheaper brands during this period, our results suggest that some of these savings were offset by faster price growth of these brands. Moreover, as headline inflation returned to pre-pandemic levels, the relative prices of cheaper options remained persistently higher even as inflationary inequality eased. This may help explain why some consumers may think that prices are “too high”: not only compared to the past, but also relative to more expensive varieties.

The ONS last updated its cheap food analysis (often referred to as the Vimes ‘shoe’ index) in October 2022. We’ve emailed to check if the project is still active. We also emailed Jack Monroe, who withdrew from public life after complaining of harassment last June. We will update the post if we receive a response from either party.