Some two-thirds of the energy used to heat buildings worldwide still depends on fossil fuels – usually in the form of a gas boiler.

Reducing this dependency is a key part of the journey to net zero. And one of the key technologies to achieve this goal is the heat pump.

Best understood as working like a refrigerator in reverse, this technology is not new but is now expanding rapidly.

How does it work?

Heat pumps draw heat from outside air or the ground to heat buildings. They run on electricity that can be produced from low-carbon sources and thus have the potential to solve one of the world’s biggest challenges: the decarbonisation of heating. Heating buildings accounts for about 10 percent of global carbon dioxide emissions, while about 60 percent of space and water heating worldwide is still provided by fossil fuels, according to the International Energy Agency.

Heat pumps work by using refrigerant gases, usually found in refrigerators and air conditioners, to transfer heat.

What are the advantages and disadvantages?

Heat pumps have two main advantages: they run on electricity, which increasingly comes from renewable sources; and are highly effective. They can typically produce 3-5 units of heat for every unit of electricity used to run the pump and can work even when it’s very cold outside.

But in most major markets they are currently more expensive to buy and install than gas boilers. Air-to-water heat pumps – the type that can be connected to radiators – are most efficient when their output is lower than that of gas boilers. This may mean that larger radiators or better insulation of the house must be installed.

They will also contribute to an increase in demand for electricity at peak times, which may require the upgrading of electricity cable networks in some areas. And refrigerant gases contribute to global warming if they escape — although experts say that when it comes to heat pumps, the problem is outweighed by the fossil fuels they displace.

Will he save the planet?

Heat pumps are increasingly seen as key to decarbonisation targets, with the IEA estimating that 875 million households will need them by 2050 to be in line with net zero targets (along with an increase in clean electricity).

Alternative low-carbon heating methods are being considered, but some, such as those using hydrogen, are less efficient and more expensive.

Apart from some supply chain bottlenecks, the key factor currently holding back further production and deployment of heat pumps is demand. This was limited by the initial cost of the equipment as well as household unfamiliarity with the technology. In the UK and some other markets, electricity is also significantly more expensive than gas, increasing operating costs. Many governments now offer subsidies to increase the consumption of heat pumps.

Has it arrived yet?

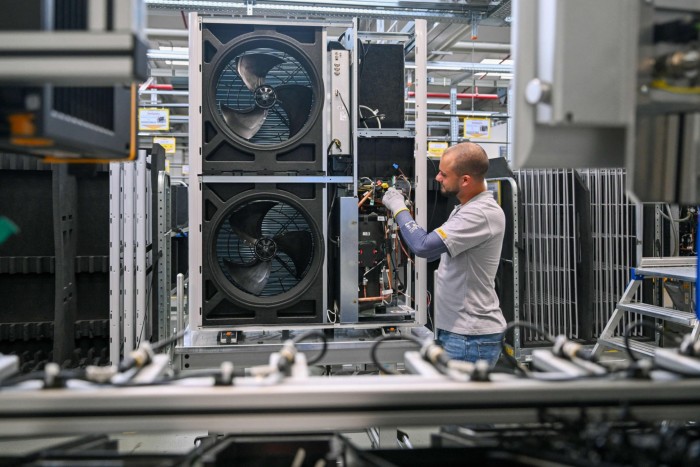

Heat pumps are an advanced technology and have been used around the world for decades. However, manufacturers are working to improve their efficiency, reduce costs, facilitate their installation in homes, enable water to be heated to higher temperatures and use refrigerants that are more environmentally friendly.

Work is also underway to understand the extent to which heat pumps can run outside of peak electricity consumption without affecting household comfort.

Installation processes are also improved. “There’s a lot of room for innovation, just making sure the installers are working at a very high level,” says Jan Rosenow, director of the NGO Regulatory Assistance Project.

An estimated 200 million heat pumps are now installed worldwide and are particularly popular in the Nordic countries. Air-to-air heat pumps, which can be used for both air conditioning and heating, are also “the norm” in some parts of China, according to the IEA.

Global sales rose 11 percent in 2022, helped by increased demand in Europe as households responded to a spike in gas prices triggered by Russia’s large-scale invasion of Ukraine. But sales of heat pumps then fell by 3 percent in 2023. By early 2023, it was supplying about 10 percent of all global heating, the IEA says.

Who are the winners and losers?

Boiler manufacturers risk a loss from any mass switch to heat pumps. However, many are also switching to the production of heat pumps.

Pipeline owners could potentially lose more as fewer households remain connected to their grid. Many advocate using hydrogen instead, or hybrid systems that include heat pumps alongside fossil fuel boilers. But the outage also raises the prospect of higher bills for those households that remain on the grid, as well as questions about who will pay the costs of decommissioning the gas.

On the contrary, the transition to heat pumps would increase the use of electrical networks. National Grid, Britain’s FTSE 100 company, has agreed to pay £7.8 billion in 2021 for Western Power Distribution, Britain’s largest electricity distribution company, in a bid to “electrify” the power system.

Who invests in it?

Government support and the scale of the potential future market mean that heat pumps are attracting investment from several sources, including traditional heat pump and boiler manufacturers expanding or setting up new production lines.

At the end of 2023, the European Heat Pump Association calculated investments worth almost 7 billion euros in heat pump production and research in Europe over the next three years.

Bosch, for example, has announced plans for a new €225 million factory in Poland to open in late 2027, part of an overall €1 billion investment in European heat pump production capacity this decade. In 2021, Canadian infrastructure giant Brookfield bought a majority stake in German heat pump installer Thermondo, and then in 2023 bought UK home repair company Homeserve. That year also saw UK financial services giant Legal and General invest £70m alongside Octopus Energy in ground source heat pump company Kensa.